Charlie's Bird

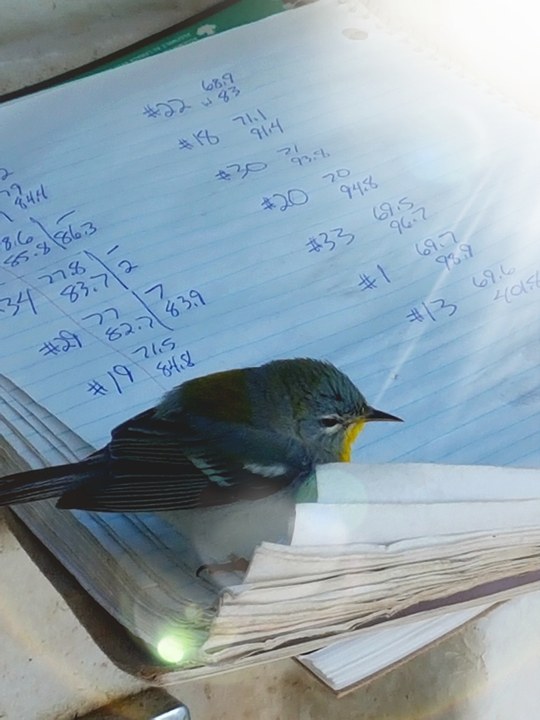

The stowaway. (KATE BOYD PHOTO)

He immediately regretted telling them.

Charlie looked around the wheelhouse again … no little bird.

What if there hadn’t been a fuzzy little bird perched upon the plywood table at which they ate their lunch every morning at 8 am?

What if his father’s 33 year old boat had finally driven him mad?

Trips to Port Hawkesbury and Stellarton to get belts and batteries and switches and an alternator, every day it seemed after they tied to the wharf.

The mildly incompetent deckhand he’d hired solely for his good looks and charm steps into the wheel house… looks around.

“Perhaps an acid flashback,” the crewman suggests.

They look at each other.

Perhaps.

Back on the deck, the crewman returns to sawing through redfish with the same dull knife Charlie will later wipe once on each side before cutting his sandwich in half to offer around.

The light, if there had ever been any, is long gone from the redfish eyes.

The vicious little beast rise from the bottom each night to hunt as schools in depths of a hundred metres on the Scotian Shelf until hauled up to gasp for air on a trawlers deck - their killing done.

Their white bottoms are the only soft spot on their armoured bodies.

So that’s where the deckhand starts each cut, yellow spawn oozing out as the blade makes its way to their spiky backbones.

“My husband’s seeing things?” asks Kate from her banding table.

Maybe.

Hopefully not.

The engine slows.

The deckhand grabs the gaff, leans over the washboard and hooks the approaching buoy.

Back to the hauler and he stares at the water’s surface.

The line winds up through the thin, ever changing border between the world above and the one below.

A border that never stops moving and shimmering and won’t let the eye peer more than a few feet into the deep’s secrets.

All the creatures hauled up from that world seem built for war.

The first trap is for a moment a phantom before it breaks the surface in a rush and stops dead before the hauler.

Clad in medieval armour, the lobsters know their own weaknesses and seek to snap off each others’ claws at the soft tissue of the joint.

Some bear scars from old battles with their kinsmen.

Aaron and Charlie working the traps. (Kate Boyd Photo)

“It’s Charlie’s bird!” exclaims Kate.

Charlie’s relief that his mind is still intact, at least for now, comes with a sigh.

“Charlie’s little bird!” says Kate with glee.

“Just what I need now,” says Charlie.

He knows he won’t hear the end of ‘Charlie’s little bird’.

He looks at the crewman, who has his mouth open to parrot Kate’s new catchphrase but appears to think better of it and just grins widely.

The bird, with a tuft of yellow feathers on its belly and fine little feet, is perched up forward on the bunk that has routered into its facing “Captain’s Bunk (Only!).”

The four bunks, built for a time when the boat might travel Nova Scotia’s coast hunting a variety of migratory species, now just house the motley assemblage of tools with which he keeps the old beast running.

The Sheldon B never travels farther than five miles from shore these days, to Charlie’s most distant lobster sets.

“Don’t disturb it, we’re too far out now for it to fly back.”

He heads back to the hauler and the work at hand with the unspoken direction that the others do the same.

And they do.

Between sets the bird bounces around Charlie in the wheelhouse, completely unafraid.

So unlike all the creatures of the depths - bait, lobsters and bycatch - that appear daily on The Sheldon B.

To survive this world it must be tough.

But to the eye it is dainty.

More something that would be given to a child for comfort than a wild animal.

And the skipper whose mind is constantly turned to hunting a specie who have neither mercy for their own kith nor kin, finds himself plotting to get this little bird safely back to shore.

It matters, somehow.

At the next set, the crewman is jamming redfish on spikes and Kate is immobilizing lobster claws with elastic bands so they can’t tear each other apart.

The little bird flutters out and onto the wheelhouse roof.

All three look up from their tasks and hold their breath.

They watch it puff its fuzzy bum feathers then take aloft and head toward Bayfield, ten miles away.

“It can’t make it,” says Charlie, turning back to the hauler.

“There’s nothing we can do for it now.”

The rest of the dump is hauled, fished and baited in silence with no wry comments about ‘Charlie’s little bird’.

The morning wears on.

Communication boiled to the required “GOT IT … OKAY … GONE” between Charlie and the crewman, signifying the gaffing of the buoy, time to push the dump overboard and the final buoy being clear of the deck.

Then it’s back.

No one saw it arrive.

But it’s in the wheelhouse again.

“Charlie’s Little Bird!”

And this time Charlie doesn’t mind.

Steaming back into the wharf, a cloud of seagulls clamor overhead waiting for them to dump their tubs of spent bait.

Their dark shadows swoop across the deck as the little yellow bird hops about the cozy wheelhouse.

The crewman dumps the dessicated mackerel and redfish over and the gulls fall upon each other in a vicious feeding frenzy.

The crewman thinks about the pregnant wife and toddler who’ll meet him at the door when he gets home in an hour.

Kate thinks about her and Charlie’s little girl in her Raggedy -Anne costume at the weekend’s dance recital.

And Charlie doesn’t think about what he is going to spend the rest of the day fixing on the boat.

He just watches the little yellow bird bouncing around the wheelhouse.

The little bird examines where Charlie dumps his traps. (KATE BOYD Photo)